Safeguarders of Heritage

The Pillars: as guardians of traditions and heritage Women are the main receptacles and practitioners of heritage in Sudanese society. They also work tirelessly to safeguard and maintain this heritage.

Wedding customs and traditions of Kordofan

Wedding customs and traditions of Kordofan

Marriage is one of the most important social events in Sudanese society with a longstanding culture of traditional wedding ceremonies across all regions, each with its specific regional rituals and traditions. Some elements of the traditional wedding ceremony have disappeared and some have evolved. In the past the gat’ al-rahat, subhiyya and jirtig elements of the traditional wedding used to be held over forty days. In more recent times it has been cut down to three days and in some cases, the entire wedding may be over in one day.

Matchmaking used to be the prerogative of people other than the bride and groom; 'The girl is to wed to her paternal cousin,’ was a common saying adhered to by many Sudanese. As girls and young women of marrying age were not allowed to leave the home, matchmakers often went around families suggesting suitable alliances. Once a match was made, men from the groom’s family would visit the bride’s family and officially ask for her hand in marriage, a request sealed with the recitation of the fatiha verse of the Quran. This is followed by golat al-khayr, women from the groom’s family go the bride’s home bearing gifts and spend the evening eating and drinking a lavish meal, a chance for the families to get to know each other more.

Once a date is set for the wedding, the groom presents the bride with her shela or dowry which consists of clothes, perfumes and jewellery. Next begins the lengthy wedding preparations and the bride succumbs to being confined at home or al-habsa. In the past, this time of isolation was used by the bride to sew and embroider furnishings for her future home; bed sheets, and handmade items of clothing for her fiancé. Preparing and furnishing the newlywed’s house was the task of the bride’s father, to signify the status of his daughter. The bride's mother prepared the various covers and kitchen staples, from cooking utensils to traditional ingredients like dried meat sharmut, onions and weka, dried okra powder. The bride would be plumped up and beautified for her wedding. Dukkhan the perfumed smoke bath the bride sits on regularly before the wedding was supervised by a woman who met certain criteria; she had to be a close relative and happy in her life and thus a good omen for the bride, protecting her against marital problems or divorce.

As the wedding approaches, a henna party is organised for the groom when a paste of henna mixed with pungent mahlabiyya or surratiyya oil is spread over his hands and feet. A large bashari style porcelain dish, known as abu najma, the star, and hilaal azrag, blue crescent, holds the henna mixture with lit candles stuck into it. Sweets, dates, sugar and salt, symbolising the steadfastness of marriage in the face of the ups and downs of life, and al-tayman incense, to ward off the evil eye, are all present on the large henna tray. One of the older wedding customs involved guests contributing a sum of money towards the wedding costs during the henna party and was known as al-shobash (is this right?) A friend or relative of the groom would start the ritual by pledging a sum of money, gold or livestock with the rest of the family and friends – men and women – then competing to outdo the rest. The person who collected the money and announced the sum paid by each person was usually a well-known local figure with a sense of humour. The custom has been replaced by the Kashif, a list of names and their cash contributions towards the wedding.

Two feasts are organised to celebrate the marriage; the groom’s family organises one as part of the henna party while the bride’s family organises one after the religious marriage ceremony, agid, performed at the bride’s house or the local mosque. Lunch, formally known as ‘the wedding feast’, is organised at the bride’s house. A procession, sera, of the groom’s party would make its way to the bride’s house with the groom at the head riding an adorned horse and wielding a sword, accompanied by his family and friends. A long time ago, the sera was made on foot, with the head of the family at the front and women beating drums and singing traditional sera songs and ululating men dancing, and incense lit all along the way. Before reaching the bride’s home, the procession would visit the graves and shrines of suffi men to receive their blessing for a happy married life. At the bride’s house, the groom’s procession would be welcomed by another crowd drumming and sprayed with water. 'Welcome, whether you come with a pound coin or an ounce of gold' the bride’s mother would say welcoming her guests. Once dinner is consumed, the bride is revealed in her full beauty, preceded by incense and ululates and heralded by her sisters and friends. Elder women give her to the groom in a ritual when the newlyweds are instructed on the sanctity of marriage and the importance of respecting each other.

In the past the bride wore a white tob with her face was covered in the distinctive silk garmasis fabric which the groom would remove so he and his family could see her face, possibly for the first time. Then the ritual of gat’ al-rahat was performed in which the thick thread tied around the bride’s waist at her engagement was cut by the groom. Sweets were tied to it so it was tossed to the young ladies as a good omen for the non-married, and afterwards the groom paid a sum of money to the lady who gave him the rahat to pass on to the bride’s mother for the last of the rituals, the bridal dance. The dance was the most anticipated event. The bride would perform scores of dances and would play a game with the groom whereby she would try to drop to the ground and avoid being caught by the groom, thus scoring a ‘goal.’

The jartig is the most important and most distinctively Sudanese part of the wedding performed to bring good luck, fertility, happiness and protection for the newlyweds. The word jartig itself is thought to come from the ancient Meroitic word qortig, qor meaning king and tig to make, i.e., make a kind.

The final part of a wedding is the ruhul when the bride moves to her new home accompanied by a large crowd singing and ululates. Two women remained with the newlyweds for a week to help serve her and the guests coming to congratulate the couple.

Marriage is one of the most important social events in Sudanese society with a longstanding culture of traditional wedding ceremonies across all regions, each with its specific regional rituals and traditions. Some elements of the traditional wedding ceremony have disappeared and some have evolved. In the past the gat’ al-rahat, subhiyya and jirtig elements of the traditional wedding used to be held over forty days. In more recent times it has been cut down to three days and in some cases, the entire wedding may be over in one day.

Matchmaking used to be the prerogative of people other than the bride and groom; 'The girl is to wed to her paternal cousin,’ was a common saying adhered to by many Sudanese. As girls and young women of marrying age were not allowed to leave the home, matchmakers often went around families suggesting suitable alliances. Once a match was made, men from the groom’s family would visit the bride’s family and officially ask for her hand in marriage, a request sealed with the recitation of the fatiha verse of the Quran. This is followed by golat al-khayr, women from the groom’s family go the bride’s home bearing gifts and spend the evening eating and drinking a lavish meal, a chance for the families to get to know each other more.

Once a date is set for the wedding, the groom presents the bride with her shela or dowry which consists of clothes, perfumes and jewellery. Next begins the lengthy wedding preparations and the bride succumbs to being confined at home or al-habsa. In the past, this time of isolation was used by the bride to sew and embroider furnishings for her future home; bed sheets, and handmade items of clothing for her fiancé. Preparing and furnishing the newlywed’s house was the task of the bride’s father, to signify the status of his daughter. The bride's mother prepared the various covers and kitchen staples, from cooking utensils to traditional ingredients like dried meat sharmut, onions and weka, dried okra powder. The bride would be plumped up and beautified for her wedding. Dukkhan the perfumed smoke bath the bride sits on regularly before the wedding was supervised by a woman who met certain criteria; she had to be a close relative and happy in her life and thus a good omen for the bride, protecting her against marital problems or divorce.

As the wedding approaches, a henna party is organised for the groom when a paste of henna mixed with pungent mahlabiyya or surratiyya oil is spread over his hands and feet. A large bashari style porcelain dish, known as abu najma, the star, and hilaal azrag, blue crescent, holds the henna mixture with lit candles stuck into it. Sweets, dates, sugar and salt, symbolising the steadfastness of marriage in the face of the ups and downs of life, and al-tayman incense, to ward off the evil eye, are all present on the large henna tray. One of the older wedding customs involved guests contributing a sum of money towards the wedding costs during the henna party and was known as al-shobash (is this right?) A friend or relative of the groom would start the ritual by pledging a sum of money, gold or livestock with the rest of the family and friends – men and women – then competing to outdo the rest. The person who collected the money and announced the sum paid by each person was usually a well-known local figure with a sense of humour. The custom has been replaced by the Kashif, a list of names and their cash contributions towards the wedding.

Two feasts are organised to celebrate the marriage; the groom’s family organises one as part of the henna party while the bride’s family organises one after the religious marriage ceremony, agid, performed at the bride’s house or the local mosque. Lunch, formally known as ‘the wedding feast’, is organised at the bride’s house. A procession, sera, of the groom’s party would make its way to the bride’s house with the groom at the head riding an adorned horse and wielding a sword, accompanied by his family and friends. A long time ago, the sera was made on foot, with the head of the family at the front and women beating drums and singing traditional sera songs and ululating men dancing, and incense lit all along the way. Before reaching the bride’s home, the procession would visit the graves and shrines of suffi men to receive their blessing for a happy married life. At the bride’s house, the groom’s procession would be welcomed by another crowd drumming and sprayed with water. 'Welcome, whether you come with a pound coin or an ounce of gold' the bride’s mother would say welcoming her guests. Once dinner is consumed, the bride is revealed in her full beauty, preceded by incense and ululates and heralded by her sisters and friends. Elder women give her to the groom in a ritual when the newlyweds are instructed on the sanctity of marriage and the importance of respecting each other.

In the past the bride wore a white tob with her face was covered in the distinctive silk garmasis fabric which the groom would remove so he and his family could see her face, possibly for the first time. Then the ritual of gat’ al-rahat was performed in which the thick thread tied around the bride’s waist at her engagement was cut by the groom. Sweets were tied to it so it was tossed to the young ladies as a good omen for the non-married, and afterwards the groom paid a sum of money to the lady who gave him the rahat to pass on to the bride’s mother for the last of the rituals, the bridal dance. The dance was the most anticipated event. The bride would perform scores of dances and would play a game with the groom whereby she would try to drop to the ground and avoid being caught by the groom, thus scoring a ‘goal.’

The jartig is the most important and most distinctively Sudanese part of the wedding performed to bring good luck, fertility, happiness and protection for the newlyweds. The word jartig itself is thought to come from the ancient Meroitic word qortig, qor meaning king and tig to make, i.e., make a kind.

The final part of a wedding is the ruhul when the bride moves to her new home accompanied by a large crowd singing and ululates. Two women remained with the newlyweds for a week to help serve her and the guests coming to congratulate the couple.

Marriage is one of the most important social events in Sudanese society with a longstanding culture of traditional wedding ceremonies across all regions, each with its specific regional rituals and traditions. Some elements of the traditional wedding ceremony have disappeared and some have evolved. In the past the gat’ al-rahat, subhiyya and jirtig elements of the traditional wedding used to be held over forty days. In more recent times it has been cut down to three days and in some cases, the entire wedding may be over in one day.

Matchmaking used to be the prerogative of people other than the bride and groom; 'The girl is to wed to her paternal cousin,’ was a common saying adhered to by many Sudanese. As girls and young women of marrying age were not allowed to leave the home, matchmakers often went around families suggesting suitable alliances. Once a match was made, men from the groom’s family would visit the bride’s family and officially ask for her hand in marriage, a request sealed with the recitation of the fatiha verse of the Quran. This is followed by golat al-khayr, women from the groom’s family go the bride’s home bearing gifts and spend the evening eating and drinking a lavish meal, a chance for the families to get to know each other more.

Once a date is set for the wedding, the groom presents the bride with her shela or dowry which consists of clothes, perfumes and jewellery. Next begins the lengthy wedding preparations and the bride succumbs to being confined at home or al-habsa. In the past, this time of isolation was used by the bride to sew and embroider furnishings for her future home; bed sheets, and handmade items of clothing for her fiancé. Preparing and furnishing the newlywed’s house was the task of the bride’s father, to signify the status of his daughter. The bride's mother prepared the various covers and kitchen staples, from cooking utensils to traditional ingredients like dried meat sharmut, onions and weka, dried okra powder. The bride would be plumped up and beautified for her wedding. Dukkhan the perfumed smoke bath the bride sits on regularly before the wedding was supervised by a woman who met certain criteria; she had to be a close relative and happy in her life and thus a good omen for the bride, protecting her against marital problems or divorce.

As the wedding approaches, a henna party is organised for the groom when a paste of henna mixed with pungent mahlabiyya or surratiyya oil is spread over his hands and feet. A large bashari style porcelain dish, known as abu najma, the star, and hilaal azrag, blue crescent, holds the henna mixture with lit candles stuck into it. Sweets, dates, sugar and salt, symbolising the steadfastness of marriage in the face of the ups and downs of life, and al-tayman incense, to ward off the evil eye, are all present on the large henna tray. One of the older wedding customs involved guests contributing a sum of money towards the wedding costs during the henna party and was known as al-shobash (is this right?) A friend or relative of the groom would start the ritual by pledging a sum of money, gold or livestock with the rest of the family and friends – men and women – then competing to outdo the rest. The person who collected the money and announced the sum paid by each person was usually a well-known local figure with a sense of humour. The custom has been replaced by the Kashif, a list of names and their cash contributions towards the wedding.

Two feasts are organised to celebrate the marriage; the groom’s family organises one as part of the henna party while the bride’s family organises one after the religious marriage ceremony, agid, performed at the bride’s house or the local mosque. Lunch, formally known as ‘the wedding feast’, is organised at the bride’s house. A procession, sera, of the groom’s party would make its way to the bride’s house with the groom at the head riding an adorned horse and wielding a sword, accompanied by his family and friends. A long time ago, the sera was made on foot, with the head of the family at the front and women beating drums and singing traditional sera songs and ululating men dancing, and incense lit all along the way. Before reaching the bride’s home, the procession would visit the graves and shrines of suffi men to receive their blessing for a happy married life. At the bride’s house, the groom’s procession would be welcomed by another crowd drumming and sprayed with water. 'Welcome, whether you come with a pound coin or an ounce of gold' the bride’s mother would say welcoming her guests. Once dinner is consumed, the bride is revealed in her full beauty, preceded by incense and ululates and heralded by her sisters and friends. Elder women give her to the groom in a ritual when the newlyweds are instructed on the sanctity of marriage and the importance of respecting each other.

In the past the bride wore a white tob with her face was covered in the distinctive silk garmasis fabric which the groom would remove so he and his family could see her face, possibly for the first time. Then the ritual of gat’ al-rahat was performed in which the thick thread tied around the bride’s waist at her engagement was cut by the groom. Sweets were tied to it so it was tossed to the young ladies as a good omen for the non-married, and afterwards the groom paid a sum of money to the lady who gave him the rahat to pass on to the bride’s mother for the last of the rituals, the bridal dance. The dance was the most anticipated event. The bride would perform scores of dances and would play a game with the groom whereby she would try to drop to the ground and avoid being caught by the groom, thus scoring a ‘goal.’

The jartig is the most important and most distinctively Sudanese part of the wedding performed to bring good luck, fertility, happiness and protection for the newlyweds. The word jartig itself is thought to come from the ancient Meroitic word qortig, qor meaning king and tig to make, i.e., make a kind.

The final part of a wedding is the ruhul when the bride moves to her new home accompanied by a large crowd singing and ululates. Two women remained with the newlyweds for a week to help serve her and the guests coming to congratulate the couple.

Griselda and children

Griselda and children

Visual artist Griselda El Tayeb MBE, travelled to Sudan in the early 1950s accompanying her husband, the eminent scholar of Arabic and Islamic Studies, Abdallah El Tayeb. The couple were returning in order for Abdallah to take up a teaching position after completing his Phd in London. During her life in Sudan, Griselda herself took up various teaching positions specialising in art and drafting school curricula on the topic. Art and painting thus formed an important part of Griselda’s life and she would draw and paint most of the places she visited and many of the people she saw. As such, much of her artwork has become a valuable record of bygone times and disappearing heritage in particular in relation to traditional Sudanese attire. Throughout her life Griselda always encouraged everyone around her to get creative and to paint, put on performances or get involved in any type of handicrafts.

In this audio clip, siblings Dua’a, 13, Osama, 15, and Aya 12 years-old, describe their relationship with their neighbour whom they call “Haboba Griselda”. This informal interview with the children was recorded at Griselda’s home at the University of Khartoum residences in the Burri neighbourhood of Khartoum, a short time after she passed away at the age of 97. By listening to the children talk about all the things they did together, it is clear how much of Griselda’s love and enthusiasm for art and creative activities has been passed on to the children. In the audio clip, the children give examples of the things Griselda taught them to draw and paint such as traditional Sudanese costumes, using potatoes as stencils to make their own wrapping paper and preparing Ramadan decorations. The children also tell of the time Griselda helped them to stage an old Sudanese folk tale; the costumes and parts they played, (including Griselda in the role of ghoul!), and how the surprise performance was well-received by their audience. By encouraging young Sudanese to observe, recreate and celebrate their surroundings and their cultural heritage, Griselda has played an important part in safeguarding this heritage for future generations.

Visual artist Griselda El Tayeb MBE, travelled to Sudan in the early 1950s accompanying her husband, the eminent scholar of Arabic and Islamic Studies, Abdallah El Tayeb. The couple were returning in order for Abdallah to take up a teaching position after completing his Phd in London. During her life in Sudan, Griselda herself took up various teaching positions specialising in art and drafting school curricula on the topic. Art and painting thus formed an important part of Griselda’s life and she would draw and paint most of the places she visited and many of the people she saw. As such, much of her artwork has become a valuable record of bygone times and disappearing heritage in particular in relation to traditional Sudanese attire. Throughout her life Griselda always encouraged everyone around her to get creative and to paint, put on performances or get involved in any type of handicrafts.

In this audio clip, siblings Dua’a, 13, Osama, 15, and Aya 12 years-old, describe their relationship with their neighbour whom they call “Haboba Griselda”. This informal interview with the children was recorded at Griselda’s home at the University of Khartoum residences in the Burri neighbourhood of Khartoum, a short time after she passed away at the age of 97. By listening to the children talk about all the things they did together, it is clear how much of Griselda’s love and enthusiasm for art and creative activities has been passed on to the children. In the audio clip, the children give examples of the things Griselda taught them to draw and paint such as traditional Sudanese costumes, using potatoes as stencils to make their own wrapping paper and preparing Ramadan decorations. The children also tell of the time Griselda helped them to stage an old Sudanese folk tale; the costumes and parts they played, (including Griselda in the role of ghoul!), and how the surprise performance was well-received by their audience. By encouraging young Sudanese to observe, recreate and celebrate their surroundings and their cultural heritage, Griselda has played an important part in safeguarding this heritage for future generations.

Visual artist Griselda El Tayeb MBE, travelled to Sudan in the early 1950s accompanying her husband, the eminent scholar of Arabic and Islamic Studies, Abdallah El Tayeb. The couple were returning in order for Abdallah to take up a teaching position after completing his Phd in London. During her life in Sudan, Griselda herself took up various teaching positions specialising in art and drafting school curricula on the topic. Art and painting thus formed an important part of Griselda’s life and she would draw and paint most of the places she visited and many of the people she saw. As such, much of her artwork has become a valuable record of bygone times and disappearing heritage in particular in relation to traditional Sudanese attire. Throughout her life Griselda always encouraged everyone around her to get creative and to paint, put on performances or get involved in any type of handicrafts.

In this audio clip, siblings Dua’a, 13, Osama, 15, and Aya 12 years-old, describe their relationship with their neighbour whom they call “Haboba Griselda”. This informal interview with the children was recorded at Griselda’s home at the University of Khartoum residences in the Burri neighbourhood of Khartoum, a short time after she passed away at the age of 97. By listening to the children talk about all the things they did together, it is clear how much of Griselda’s love and enthusiasm for art and creative activities has been passed on to the children. In the audio clip, the children give examples of the things Griselda taught them to draw and paint such as traditional Sudanese costumes, using potatoes as stencils to make their own wrapping paper and preparing Ramadan decorations. The children also tell of the time Griselda helped them to stage an old Sudanese folk tale; the costumes and parts they played, (including Griselda in the role of ghoul!), and how the surprise performance was well-received by their audience. By encouraging young Sudanese to observe, recreate and celebrate their surroundings and their cultural heritage, Griselda has played an important part in safeguarding this heritage for future generations.

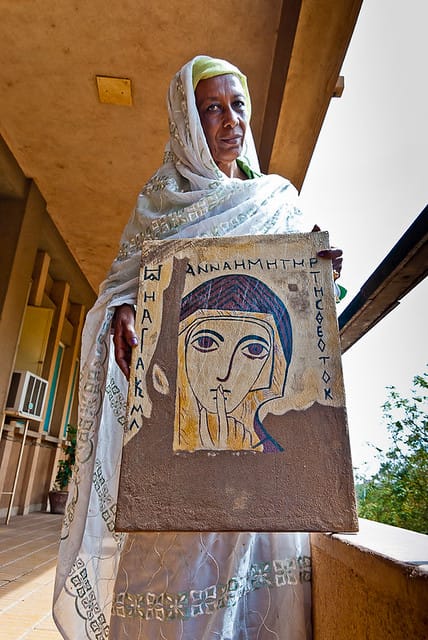

Fatima Mohamed al-Hasan

Fatima Mohamed al-Hasan

Fatima Mohamed al-Hasan was a vocal advocate for human and women’s rights in Darfur with a passionate interest in Sudanese heritage and handicrafts. In 2010 Fatima was arrested for writing a book in which she likened the abuses at the Iraqi Abu Ghraib prison to what the residents of Kaili and Shatai villages, in southern Darfur, had suffered at the hands of government authorities. She was also briefly detained on accusations of cooperating with the International Criminal Court that was investigating Darfur crimes. Fatima’s strong positions in support of the people of Darfur and in particular its women, earned her a place on numerous delegations to the Darfur peace talks in Doha and Abuja. This representation of Darfur and its women extended to many workshops and conferences she attended locally and abroad. As a result, Fatima, who started her career as a school teacher also occupied several government posts such as the general manager of tourism and heritage at the ministry of social and cultural affairs in South Darfur State, 1994, head of the department of traditional handicrafts at the ministry of economic affairs in 1999 and minister for youth, sport, environment and tourism in 2012.

Alongside her official work, Fatima played a significant role in the voluntary and charitable sectors in Darfur establishing the Mandola House for heritage, culture and arts in 1987, headed the Bakhita charity organisation for women’s development and child protection in South Darfur in 1988, and founded the Women’s Cultural and Sports’ Club in Nyala in 2007. Fatima also presented a radio programme on popular folklore on Radio Nyala that broadcast from southern Darfur.

The preservation and showcasing of cultural heritage and traditional handicrafts was a key part of Fatima’s vision for peaceful coexistence and for unifying warring sides in the Darfur conflict. Her emphasis on heading the language of the popular, traditional and cultural was often emphasised at peace talks as a means of achieving a successful peace process. In 1985, Fatima established the first space dedicated for women at the Darfur Women’s Museum in Nyala. Over the years the museum grew to house thousands of cultural artefacts and host dozens of heritage related events and is thus a fitting legacy for the courageous woman who worked tirelessly for Darfur and who passed away in 2023.

Fatima Mohamed al-Hasan was a vocal advocate for human and women’s rights in Darfur with a passionate interest in Sudanese heritage and handicrafts. In 2010 Fatima was arrested for writing a book in which she likened the abuses at the Iraqi Abu Ghraib prison to what the residents of Kaili and Shatai villages, in southern Darfur, had suffered at the hands of government authorities. She was also briefly detained on accusations of cooperating with the International Criminal Court that was investigating Darfur crimes. Fatima’s strong positions in support of the people of Darfur and in particular its women, earned her a place on numerous delegations to the Darfur peace talks in Doha and Abuja. This representation of Darfur and its women extended to many workshops and conferences she attended locally and abroad. As a result, Fatima, who started her career as a school teacher also occupied several government posts such as the general manager of tourism and heritage at the ministry of social and cultural affairs in South Darfur State, 1994, head of the department of traditional handicrafts at the ministry of economic affairs in 1999 and minister for youth, sport, environment and tourism in 2012.

Alongside her official work, Fatima played a significant role in the voluntary and charitable sectors in Darfur establishing the Mandola House for heritage, culture and arts in 1987, headed the Bakhita charity organisation for women’s development and child protection in South Darfur in 1988, and founded the Women’s Cultural and Sports’ Club in Nyala in 2007. Fatima also presented a radio programme on popular folklore on Radio Nyala that broadcast from southern Darfur.

The preservation and showcasing of cultural heritage and traditional handicrafts was a key part of Fatima’s vision for peaceful coexistence and for unifying warring sides in the Darfur conflict. Her emphasis on heading the language of the popular, traditional and cultural was often emphasised at peace talks as a means of achieving a successful peace process. In 1985, Fatima established the first space dedicated for women at the Darfur Women’s Museum in Nyala. Over the years the museum grew to house thousands of cultural artefacts and host dozens of heritage related events and is thus a fitting legacy for the courageous woman who worked tirelessly for Darfur and who passed away in 2023.

Fatima Mohamed al-Hasan was a vocal advocate for human and women’s rights in Darfur with a passionate interest in Sudanese heritage and handicrafts. In 2010 Fatima was arrested for writing a book in which she likened the abuses at the Iraqi Abu Ghraib prison to what the residents of Kaili and Shatai villages, in southern Darfur, had suffered at the hands of government authorities. She was also briefly detained on accusations of cooperating with the International Criminal Court that was investigating Darfur crimes. Fatima’s strong positions in support of the people of Darfur and in particular its women, earned her a place on numerous delegations to the Darfur peace talks in Doha and Abuja. This representation of Darfur and its women extended to many workshops and conferences she attended locally and abroad. As a result, Fatima, who started her career as a school teacher also occupied several government posts such as the general manager of tourism and heritage at the ministry of social and cultural affairs in South Darfur State, 1994, head of the department of traditional handicrafts at the ministry of economic affairs in 1999 and minister for youth, sport, environment and tourism in 2012.

Alongside her official work, Fatima played a significant role in the voluntary and charitable sectors in Darfur establishing the Mandola House for heritage, culture and arts in 1987, headed the Bakhita charity organisation for women’s development and child protection in South Darfur in 1988, and founded the Women’s Cultural and Sports’ Club in Nyala in 2007. Fatima also presented a radio programme on popular folklore on Radio Nyala that broadcast from southern Darfur.

The preservation and showcasing of cultural heritage and traditional handicrafts was a key part of Fatima’s vision for peaceful coexistence and for unifying warring sides in the Darfur conflict. Her emphasis on heading the language of the popular, traditional and cultural was often emphasised at peace talks as a means of achieving a successful peace process. In 1985, Fatima established the first space dedicated for women at the Darfur Women’s Museum in Nyala. Over the years the museum grew to house thousands of cultural artefacts and host dozens of heritage related events and is thus a fitting legacy for the courageous woman who worked tirelessly for Darfur and who passed away in 2023.

Wedding preparations

Wedding preparations

Anyone who knows Sudan will be familiar with the sensory overload that is a Sudanese wedding. The senses are bombarded with colours, smells, tastes, sounds and textures in whichever part of the country you happen to be attending this occasion. It is an organised cacophony the rumbles of which begin rolling weeks before the day itself, rising to a crescendo on the days of the wedding, jirtig and subhiyya. As the excitement fades out gradually over the following days, the slow meticulous post-mortem is performed by the close relatives who have stayed behind, lounging on their angarebs sipping coffee; how well was the wedding organised (or not), who came (or didn’t), and what they were wearing and most importantly, was everyone who came, fed?

While this rollercoaster wave of emotions brought on by this event is an enduring feature of Sudanese weddings, some of the traditions associated with the ceremony have died out or changed over time.

One such change has been what Sudan’s riverain bride, the arous, wears during the subhiyya, the traditional Sudanese ceremony when she dances the sensual ragis al arus. A bare-chested bride, dressed only in a rahat skirt of leather strips attached to a waistband, performing in front of male and female neighbours and relatives was the norm in the early 1900s. Then, the bride was put on display to show that she was unblemished and had firm breasts. By mid-century, the rahat gradually disappeared to be worn under a short dress that covered the arous’ breasts. With the State dictating what women wore from 1983 onwards, and the imposition of Islamic dress codes, the mingling of sexes at weddings was deemed unacceptable and dances were attended only by women folk and the rahat was eventually entirely dropped from the arous’ outfit. More recently, further daring and creative dancing outfits, showing off more of the arous have been making a comeback. This latest version of ragis al arus is strictly guarded by policewomen who confiscate the mobile phones of the female audience to preserve the bride’s modesty and stop the filming and broadcast of her scantily dressed body.

The leather rahat of olden days has gone and the degree to which an arous’ body is on display as she dances, has been changing, influenced by varying fashion trends or as a result of social, political and economic forces. But in the event of a total rupture to everyday life as a result for example, of the current war, how will this most vibrant of Sudanese living heritage be affected? Will the subhiyyah and ragis arous continue to be performed or will they be substituted by another form of cultural expression? And will displaced communities have the knowledge and collective memory to pass down these traditions? These are some of the questions that will only be answered with time. In the meantime, it is up to us to talk about, write and document how we celebrate weddings and to keep remembering all the smells, sounds, colours and tastes of the subhiyya and ragis al arous.

Cover picture © Yousif Alshikh

Anyone who knows Sudan will be familiar with the sensory overload that is a Sudanese wedding. The senses are bombarded with colours, smells, tastes, sounds and textures in whichever part of the country you happen to be attending this occasion. It is an organised cacophony the rumbles of which begin rolling weeks before the day itself, rising to a crescendo on the days of the wedding, jirtig and subhiyya. As the excitement fades out gradually over the following days, the slow meticulous post-mortem is performed by the close relatives who have stayed behind, lounging on their angarebs sipping coffee; how well was the wedding organised (or not), who came (or didn’t), and what they were wearing and most importantly, was everyone who came, fed?

While this rollercoaster wave of emotions brought on by this event is an enduring feature of Sudanese weddings, some of the traditions associated with the ceremony have died out or changed over time.

One such change has been what Sudan’s riverain bride, the arous, wears during the subhiyya, the traditional Sudanese ceremony when she dances the sensual ragis al arus. A bare-chested bride, dressed only in a rahat skirt of leather strips attached to a waistband, performing in front of male and female neighbours and relatives was the norm in the early 1900s. Then, the bride was put on display to show that she was unblemished and had firm breasts. By mid-century, the rahat gradually disappeared to be worn under a short dress that covered the arous’ breasts. With the State dictating what women wore from 1983 onwards, and the imposition of Islamic dress codes, the mingling of sexes at weddings was deemed unacceptable and dances were attended only by women folk and the rahat was eventually entirely dropped from the arous’ outfit. More recently, further daring and creative dancing outfits, showing off more of the arous have been making a comeback. This latest version of ragis al arus is strictly guarded by policewomen who confiscate the mobile phones of the female audience to preserve the bride’s modesty and stop the filming and broadcast of her scantily dressed body.

The leather rahat of olden days has gone and the degree to which an arous’ body is on display as she dances, has been changing, influenced by varying fashion trends or as a result of social, political and economic forces. But in the event of a total rupture to everyday life as a result for example, of the current war, how will this most vibrant of Sudanese living heritage be affected? Will the subhiyyah and ragis arous continue to be performed or will they be substituted by another form of cultural expression? And will displaced communities have the knowledge and collective memory to pass down these traditions? These are some of the questions that will only be answered with time. In the meantime, it is up to us to talk about, write and document how we celebrate weddings and to keep remembering all the smells, sounds, colours and tastes of the subhiyya and ragis al arous.

Cover picture © Yousif Alshikh

Anyone who knows Sudan will be familiar with the sensory overload that is a Sudanese wedding. The senses are bombarded with colours, smells, tastes, sounds and textures in whichever part of the country you happen to be attending this occasion. It is an organised cacophony the rumbles of which begin rolling weeks before the day itself, rising to a crescendo on the days of the wedding, jirtig and subhiyya. As the excitement fades out gradually over the following days, the slow meticulous post-mortem is performed by the close relatives who have stayed behind, lounging on their angarebs sipping coffee; how well was the wedding organised (or not), who came (or didn’t), and what they were wearing and most importantly, was everyone who came, fed?

While this rollercoaster wave of emotions brought on by this event is an enduring feature of Sudanese weddings, some of the traditions associated with the ceremony have died out or changed over time.

One such change has been what Sudan’s riverain bride, the arous, wears during the subhiyya, the traditional Sudanese ceremony when she dances the sensual ragis al arus. A bare-chested bride, dressed only in a rahat skirt of leather strips attached to a waistband, performing in front of male and female neighbours and relatives was the norm in the early 1900s. Then, the bride was put on display to show that she was unblemished and had firm breasts. By mid-century, the rahat gradually disappeared to be worn under a short dress that covered the arous’ breasts. With the State dictating what women wore from 1983 onwards, and the imposition of Islamic dress codes, the mingling of sexes at weddings was deemed unacceptable and dances were attended only by women folk and the rahat was eventually entirely dropped from the arous’ outfit. More recently, further daring and creative dancing outfits, showing off more of the arous have been making a comeback. This latest version of ragis al arus is strictly guarded by policewomen who confiscate the mobile phones of the female audience to preserve the bride’s modesty and stop the filming and broadcast of her scantily dressed body.

The leather rahat of olden days has gone and the degree to which an arous’ body is on display as she dances, has been changing, influenced by varying fashion trends or as a result of social, political and economic forces. But in the event of a total rupture to everyday life as a result for example, of the current war, how will this most vibrant of Sudanese living heritage be affected? Will the subhiyyah and ragis arous continue to be performed or will they be substituted by another form of cultural expression? And will displaced communities have the knowledge and collective memory to pass down these traditions? These are some of the questions that will only be answered with time. In the meantime, it is up to us to talk about, write and document how we celebrate weddings and to keep remembering all the smells, sounds, colours and tastes of the subhiyya and ragis al arous.

Cover picture © Yousif Alshikh

Sudanese women in culture

Sudanese women in culture

Dr. Niemat Ragab

Cultural and Social Anthropology and Folklore

She is an Assistant Professor with more than 25 years of experience teaching Sociology and Social Anthropology in universities in Sudan and the UAE. She participated in institutionalizing the Department of Sociology at Al Neelain University. Her areas of special interest include Sociology, Social Theory, Methods of SocialResearch, Medical Sociology, Social and Cultural Anthropology, SocialPsychology, Urban Sociology, Local Communities Studies, Family and Women Studies, Folklore, Afro-Asian Studies, and History of UAE Society.

Tamador Gibreel

Actress, Director, and Mental Health Clinician

An actress,director, author, poet, and painter. Tamador Gibrel earned a BA in Acting and Direction from Sudan University. She has several radios, television and theatre works. In the early 90s, she moved to the US and formed “Arayes Al-Nile” band to combat racism. She did standup comedy and during Covid she did Zoom theater.

Nadia Aldaw

TV / RadioPresenter

She Majored in Media and Public Relations and has researched the presence of language and heritage on Sudanese radios. Her heritage research focuses on Baggara tribes in Kordofan, especially Hawazma. Her radio programs discussed nomadic communities. She also documents the elements of nomadic heritage. Multiple television and radio channels hosted Nadia as a Sudanese heritage researcher.

Omnia Shawkat

Journalist

Journalist, digital stories, and cross-cultural curator. Co-founder and manager of the cultural online platform Andariya, based in Sudan, South Sudan and other countries in East Africa and the Horn of Africa. Omnia worked in the environment and development field for six years before starting the platform. She was nominated among the top nine women tech innovators in Africa by IT News and among the top ten leading women in tech in the MENA by OpenLETR.

Naba Salah

Feminist / GenderRights Activist

Naba is the coordinator of the “Pad Needed, Dignity Seeded” initiative. She’s an advocate and campaigner for ending gender-based violence. Naba has developed a deep interest in traditions, customs, folklore, girls’ songs, and local proverbs, associating this heritage with a feminist perspective. Naba currently documents local Sudanese proverbs in graphic designs and posts them online to engage friends and followers in conversations on the origins and meanings of these proverbs and sayings.

Dr. Niemat Ragab

Cultural and Social Anthropology and Folklore

She is an Assistant Professor with more than 25 years of experience teaching Sociology and Social Anthropology in universities in Sudan and the UAE. She participated in institutionalizing the Department of Sociology at Al Neelain University. Her areas of special interest include Sociology, Social Theory, Methods of SocialResearch, Medical Sociology, Social and Cultural Anthropology, SocialPsychology, Urban Sociology, Local Communities Studies, Family and Women Studies, Folklore, Afro-Asian Studies, and History of UAE Society.

Tamador Gibreel

Actress, Director, and Mental Health Clinician

An actress,director, author, poet, and painter. Tamador Gibrel earned a BA in Acting and Direction from Sudan University. She has several radios, television and theatre works. In the early 90s, she moved to the US and formed “Arayes Al-Nile” band to combat racism. She did standup comedy and during Covid she did Zoom theater.

Nadia Aldaw

TV / RadioPresenter

She Majored in Media and Public Relations and has researched the presence of language and heritage on Sudanese radios. Her heritage research focuses on Baggara tribes in Kordofan, especially Hawazma. Her radio programs discussed nomadic communities. She also documents the elements of nomadic heritage. Multiple television and radio channels hosted Nadia as a Sudanese heritage researcher.

Omnia Shawkat

Journalist

Journalist, digital stories, and cross-cultural curator. Co-founder and manager of the cultural online platform Andariya, based in Sudan, South Sudan and other countries in East Africa and the Horn of Africa. Omnia worked in the environment and development field for six years before starting the platform. She was nominated among the top nine women tech innovators in Africa by IT News and among the top ten leading women in tech in the MENA by OpenLETR.

Naba Salah

Feminist / GenderRights Activist

Naba is the coordinator of the “Pad Needed, Dignity Seeded” initiative. She’s an advocate and campaigner for ending gender-based violence. Naba has developed a deep interest in traditions, customs, folklore, girls’ songs, and local proverbs, associating this heritage with a feminist perspective. Naba currently documents local Sudanese proverbs in graphic designs and posts them online to engage friends and followers in conversations on the origins and meanings of these proverbs and sayings.

Dr. Niemat Ragab

Cultural and Social Anthropology and Folklore

She is an Assistant Professor with more than 25 years of experience teaching Sociology and Social Anthropology in universities in Sudan and the UAE. She participated in institutionalizing the Department of Sociology at Al Neelain University. Her areas of special interest include Sociology, Social Theory, Methods of SocialResearch, Medical Sociology, Social and Cultural Anthropology, SocialPsychology, Urban Sociology, Local Communities Studies, Family and Women Studies, Folklore, Afro-Asian Studies, and History of UAE Society.

Tamador Gibreel

Actress, Director, and Mental Health Clinician

An actress,director, author, poet, and painter. Tamador Gibrel earned a BA in Acting and Direction from Sudan University. She has several radios, television and theatre works. In the early 90s, she moved to the US and formed “Arayes Al-Nile” band to combat racism. She did standup comedy and during Covid she did Zoom theater.

Nadia Aldaw

TV / RadioPresenter

She Majored in Media and Public Relations and has researched the presence of language and heritage on Sudanese radios. Her heritage research focuses on Baggara tribes in Kordofan, especially Hawazma. Her radio programs discussed nomadic communities. She also documents the elements of nomadic heritage. Multiple television and radio channels hosted Nadia as a Sudanese heritage researcher.

Omnia Shawkat

Journalist

Journalist, digital stories, and cross-cultural curator. Co-founder and manager of the cultural online platform Andariya, based in Sudan, South Sudan and other countries in East Africa and the Horn of Africa. Omnia worked in the environment and development field for six years before starting the platform. She was nominated among the top nine women tech innovators in Africa by IT News and among the top ten leading women in tech in the MENA by OpenLETR.

Naba Salah

Feminist / GenderRights Activist

Naba is the coordinator of the “Pad Needed, Dignity Seeded” initiative. She’s an advocate and campaigner for ending gender-based violence. Naba has developed a deep interest in traditions, customs, folklore, girls’ songs, and local proverbs, associating this heritage with a feminist perspective. Naba currently documents local Sudanese proverbs in graphic designs and posts them online to engage friends and followers in conversations on the origins and meanings of these proverbs and sayings.

Braids Of Identity

Braids Of Identity

Film documentaries play a vital role in preserving heritage, serving as a key strategy for raising awareness and documenting important cultural practices. The film "Braids of Identity," created by director and researcher Hafsa Borai, focuses on the craft of Sudanese hair braiding. It explores the history, social and economic significance, and the challenges threatening the continuity of this art form. This film is an extension of the short documentaries produced by the project team.

It highlighted the importance of preserving Sudanese heritage and its role in enhancing the resilience and adaptability of the people. Many elements of living heritage have become part of daily life amid crises. Traditional medicine has replaced clinics, jubraka has taken the place of farms, dara and masid have become alternatives to restaurants, and grandmothers' storytelling has replaced cartoon series. Traditional crafts, such as the hair-braiding craft showcased in this film, have also provided livelihoods for many displaced individuals both within and outside Sudan.

One of the most effective ways to protect living heritage is through documentation, raising awareness, and identifying the risks threatening its continuity. In this context, cinema and documentary films play a crucial role in spreading awareness about the importance of heritage and possible solutions to protect it. Through the lens of cinema, customs, traditions, and cultural practices can be documented visually and audibly, allowing present and future generations to understand their deep significance. Films also shed light on local communities, open doors for cultural dialogue, and contribute to sharing heritage on a global scale, thereby strengthening support for its preservation.

One of the individuals who recognized the great value of this role is the young filmmaker Hafsa Borai, who conceived the idea of the film Braids of Identity. This film tells the story of the history of the hair-braiding craft in Sudan, highlighting its significance in society and the challenges it faces. Through her research and creative efforts, she has presented us with this remarkable artistic work, which we eagerly anticipate watching today.

Cover picture © Amani Basheer

Film documentaries play a vital role in preserving heritage, serving as a key strategy for raising awareness and documenting important cultural practices. The film "Braids of Identity," created by director and researcher Hafsa Borai, focuses on the craft of Sudanese hair braiding. It explores the history, social and economic significance, and the challenges threatening the continuity of this art form. This film is an extension of the short documentaries produced by the project team.

It highlighted the importance of preserving Sudanese heritage and its role in enhancing the resilience and adaptability of the people. Many elements of living heritage have become part of daily life amid crises. Traditional medicine has replaced clinics, jubraka has taken the place of farms, dara and masid have become alternatives to restaurants, and grandmothers' storytelling has replaced cartoon series. Traditional crafts, such as the hair-braiding craft showcased in this film, have also provided livelihoods for many displaced individuals both within and outside Sudan.

One of the most effective ways to protect living heritage is through documentation, raising awareness, and identifying the risks threatening its continuity. In this context, cinema and documentary films play a crucial role in spreading awareness about the importance of heritage and possible solutions to protect it. Through the lens of cinema, customs, traditions, and cultural practices can be documented visually and audibly, allowing present and future generations to understand their deep significance. Films also shed light on local communities, open doors for cultural dialogue, and contribute to sharing heritage on a global scale, thereby strengthening support for its preservation.

One of the individuals who recognized the great value of this role is the young filmmaker Hafsa Borai, who conceived the idea of the film Braids of Identity. This film tells the story of the history of the hair-braiding craft in Sudan, highlighting its significance in society and the challenges it faces. Through her research and creative efforts, she has presented us with this remarkable artistic work, which we eagerly anticipate watching today.

Cover picture © Amani Basheer

Film documentaries play a vital role in preserving heritage, serving as a key strategy for raising awareness and documenting important cultural practices. The film "Braids of Identity," created by director and researcher Hafsa Borai, focuses on the craft of Sudanese hair braiding. It explores the history, social and economic significance, and the challenges threatening the continuity of this art form. This film is an extension of the short documentaries produced by the project team.

It highlighted the importance of preserving Sudanese heritage and its role in enhancing the resilience and adaptability of the people. Many elements of living heritage have become part of daily life amid crises. Traditional medicine has replaced clinics, jubraka has taken the place of farms, dara and masid have become alternatives to restaurants, and grandmothers' storytelling has replaced cartoon series. Traditional crafts, such as the hair-braiding craft showcased in this film, have also provided livelihoods for many displaced individuals both within and outside Sudan.

One of the most effective ways to protect living heritage is through documentation, raising awareness, and identifying the risks threatening its continuity. In this context, cinema and documentary films play a crucial role in spreading awareness about the importance of heritage and possible solutions to protect it. Through the lens of cinema, customs, traditions, and cultural practices can be documented visually and audibly, allowing present and future generations to understand their deep significance. Films also shed light on local communities, open doors for cultural dialogue, and contribute to sharing heritage on a global scale, thereby strengthening support for its preservation.

One of the individuals who recognized the great value of this role is the young filmmaker Hafsa Borai, who conceived the idea of the film Braids of Identity. This film tells the story of the history of the hair-braiding craft in Sudan, highlighting its significance in society and the challenges it faces. Through her research and creative efforts, she has presented us with this remarkable artistic work, which we eagerly anticipate watching today.

Cover picture © Amani Basheer

Women's Archives

Women's Archives

"My heart broke, my tears poured... Tonight, the journey—be a moonlight in this train."

"North, East, South, and West... Please stop war and let peace prevail on earth."

These lyrics, sung by the artist Aisha Al-Fulatia in her famous song "Yajo A'edeen" (They Will Come Back), were written and composed to honor the Sudanese Allied Forces troops who fought in World War II. Although the song originally blended celebratory, encouraging, and emotional tones, it has gained significant documentary value over time, offering insight into both private and public experiences of that era.

In this two-part episode, we explore how Sudanese women have used songs, poetry, and fashion to document historical, social, environmental, and political events in Sudan—and how these expressions have, in turn, been documented.

The second season of Khartoum Podcast was produced as part of the #OurHeritageOurSudancampaign, funded by the Safeguarding Sudan’s Living Heritage project.

Speakers in the episode:

Dr. Mahasin Yousif, a social historian, researcher and interested in studying Sudanese history.

Sarah El-Nager, a journalist, researcher and writer, working on several projects related to Sudanese culture and heritage, editor of the book Regional Folk Costumes of the Sudan by Griselda El Tayib.

Iyas Hassan, founding partner in Jeely Studio, lecturer, and production manager of TV studios.

Reem Abbas, a feminist activist, journalist, writer and researcher. Interested in women's issues, land, and resource conflict in Sudan.

Production Team:

Presenter: Azza Mohamed

Research and editing: Roaa Ismail

Script writing: Roaa Ismail

Production management: Zainab Gaafar

Sound engineering: Roaa Ismail

Music: Al-Zain Studio

Release date:30 January 2025

Cover poster by Amna Elidreesy

"My heart broke, my tears poured... Tonight, the journey—be a moonlight in this train."

"North, East, South, and West... Please stop war and let peace prevail on earth."

These lyrics, sung by the artist Aisha Al-Fulatia in her famous song "Yajo A'edeen" (They Will Come Back), were written and composed to honor the Sudanese Allied Forces troops who fought in World War II. Although the song originally blended celebratory, encouraging, and emotional tones, it has gained significant documentary value over time, offering insight into both private and public experiences of that era.

In this two-part episode, we explore how Sudanese women have used songs, poetry, and fashion to document historical, social, environmental, and political events in Sudan—and how these expressions have, in turn, been documented.

The second season of Khartoum Podcast was produced as part of the #OurHeritageOurSudancampaign, funded by the Safeguarding Sudan’s Living Heritage project.

Speakers in the episode:

Dr. Mahasin Yousif, a social historian, researcher and interested in studying Sudanese history.

Sarah El-Nager, a journalist, researcher and writer, working on several projects related to Sudanese culture and heritage, editor of the book Regional Folk Costumes of the Sudan by Griselda El Tayib.

Iyas Hassan, founding partner in Jeely Studio, lecturer, and production manager of TV studios.

Reem Abbas, a feminist activist, journalist, writer and researcher. Interested in women's issues, land, and resource conflict in Sudan.

Production Team:

Presenter: Azza Mohamed

Research and editing: Roaa Ismail

Script writing: Roaa Ismail

Production management: Zainab Gaafar

Sound engineering: Roaa Ismail

Music: Al-Zain Studio

Release date:30 January 2025

Cover poster by Amna Elidreesy

"My heart broke, my tears poured... Tonight, the journey—be a moonlight in this train."

"North, East, South, and West... Please stop war and let peace prevail on earth."

These lyrics, sung by the artist Aisha Al-Fulatia in her famous song "Yajo A'edeen" (They Will Come Back), were written and composed to honor the Sudanese Allied Forces troops who fought in World War II. Although the song originally blended celebratory, encouraging, and emotional tones, it has gained significant documentary value over time, offering insight into both private and public experiences of that era.

In this two-part episode, we explore how Sudanese women have used songs, poetry, and fashion to document historical, social, environmental, and political events in Sudan—and how these expressions have, in turn, been documented.

The second season of Khartoum Podcast was produced as part of the #OurHeritageOurSudancampaign, funded by the Safeguarding Sudan’s Living Heritage project.

Speakers in the episode:

Dr. Mahasin Yousif, a social historian, researcher and interested in studying Sudanese history.

Sarah El-Nager, a journalist, researcher and writer, working on several projects related to Sudanese culture and heritage, editor of the book Regional Folk Costumes of the Sudan by Griselda El Tayib.

Iyas Hassan, founding partner in Jeely Studio, lecturer, and production manager of TV studios.

Reem Abbas, a feminist activist, journalist, writer and researcher. Interested in women's issues, land, and resource conflict in Sudan.

Production Team:

Presenter: Azza Mohamed

Research and editing: Roaa Ismail

Script writing: Roaa Ismail

Production management: Zainab Gaafar

Sound engineering: Roaa Ismail

Music: Al-Zain Studio

Release date:30 January 2025

Cover poster by Amna Elidreesy

Old sweet box

Old sweet box

An old sweet box, many would recognise seeing it in their homes, used to store everything from eid biscuits, to incense “bakhoor” and most commonly, sewing kits!

NWM-0000279

Darfur Women’s Museum

An old sweet box, many would recognise seeing it in their homes, used to store everything from eid biscuits, to incense “bakhoor” and most commonly, sewing kits!

NWM-0000279

Darfur Women’s Museum

An old sweet box, many would recognise seeing it in their homes, used to store everything from eid biscuits, to incense “bakhoor” and most commonly, sewing kits!

NWM-0000279

Darfur Women’s Museum

The woman who documented history in silence

The woman who documented history in silence

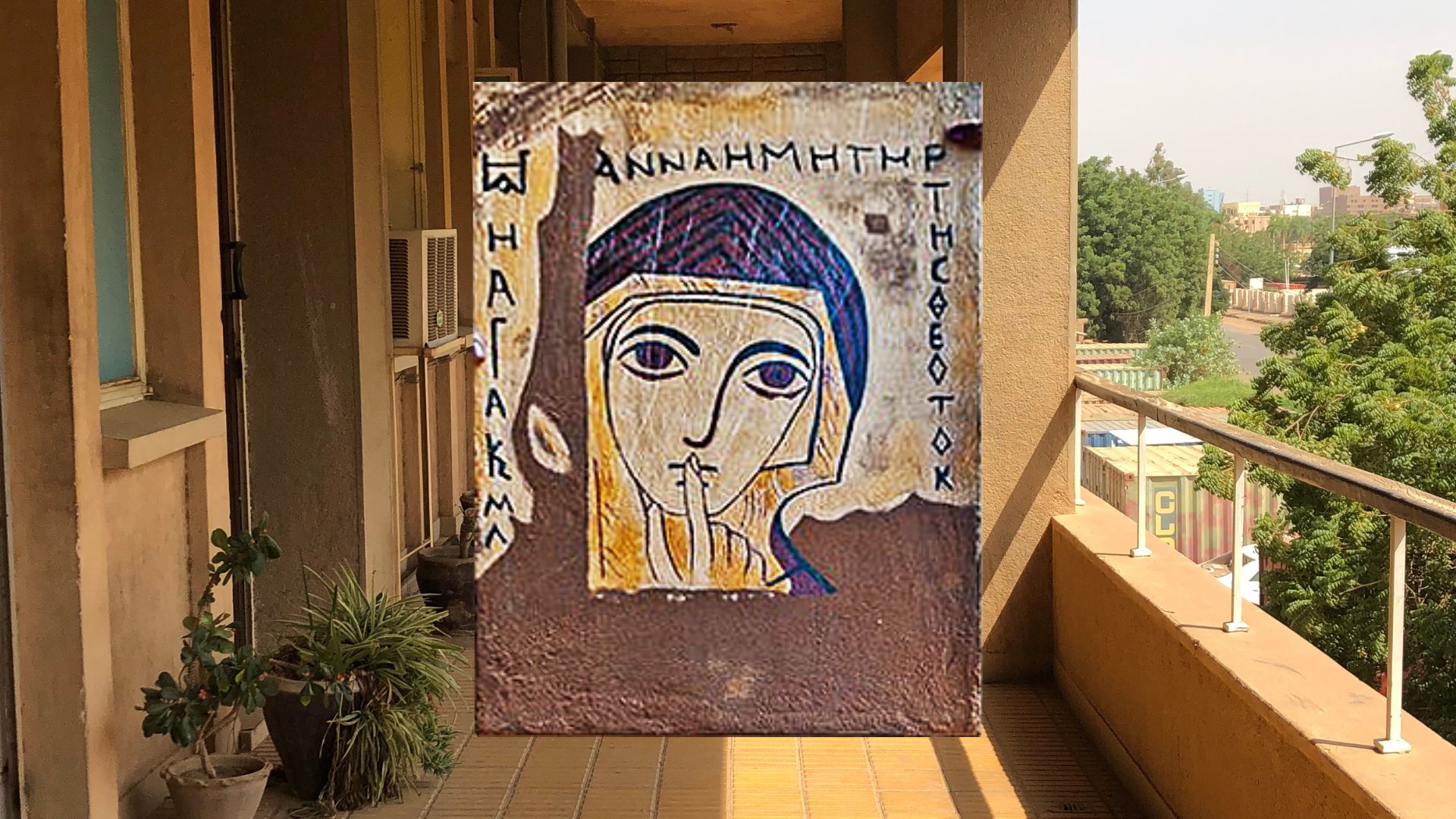

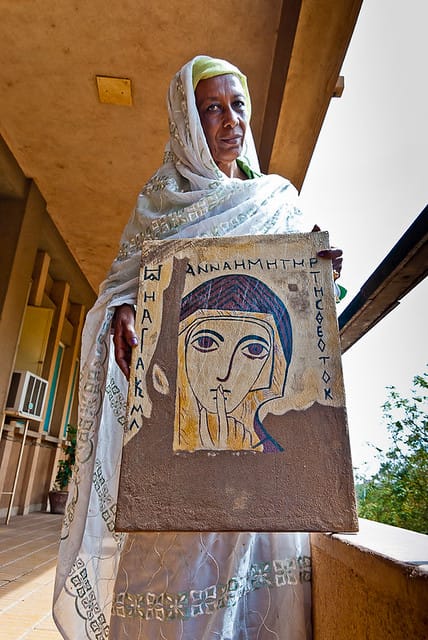

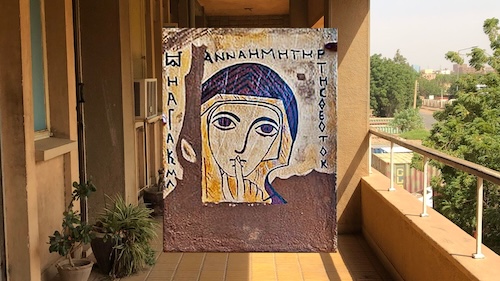

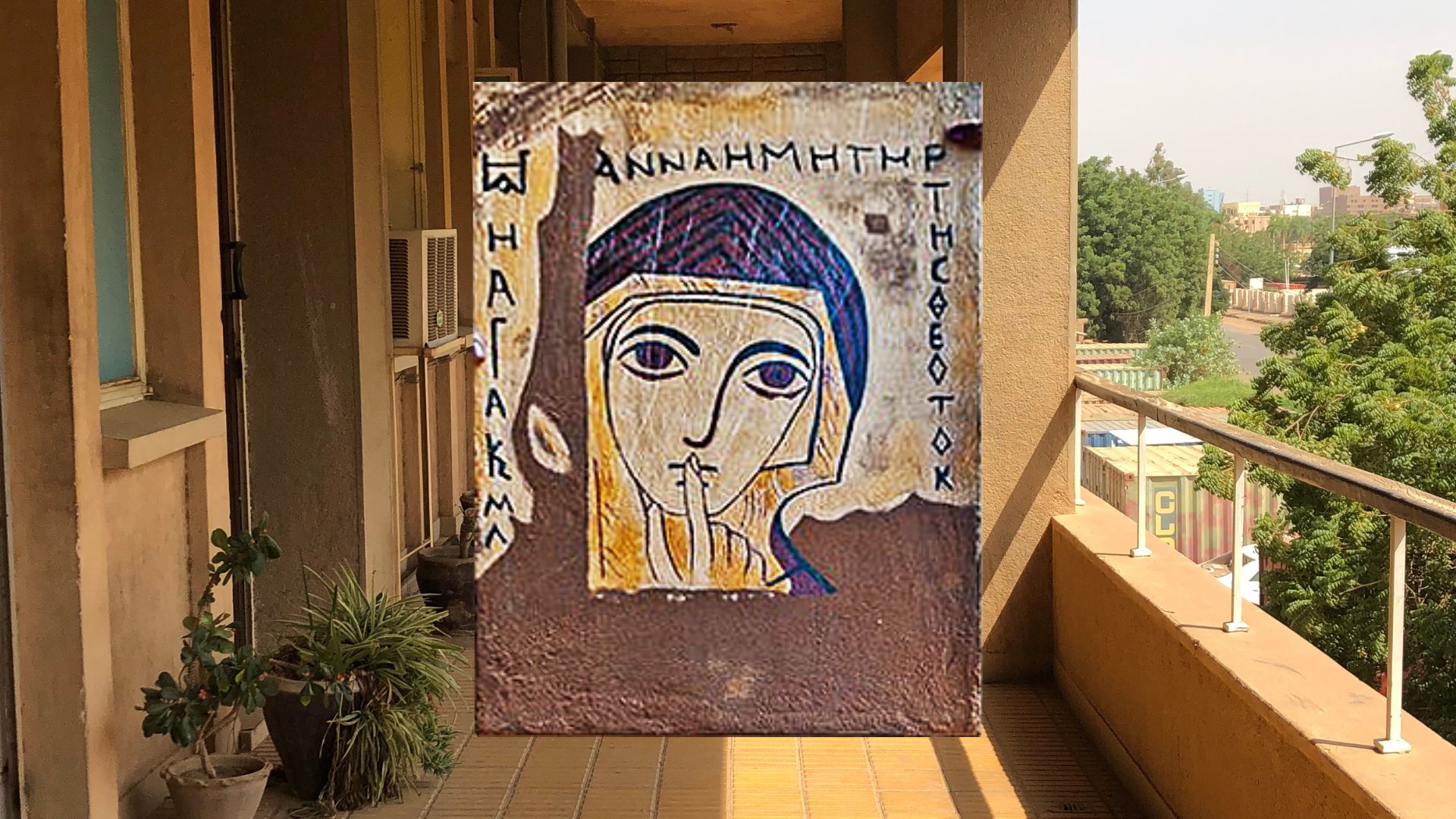

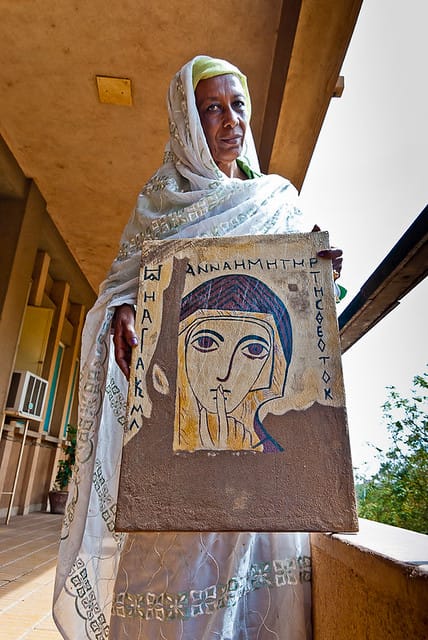

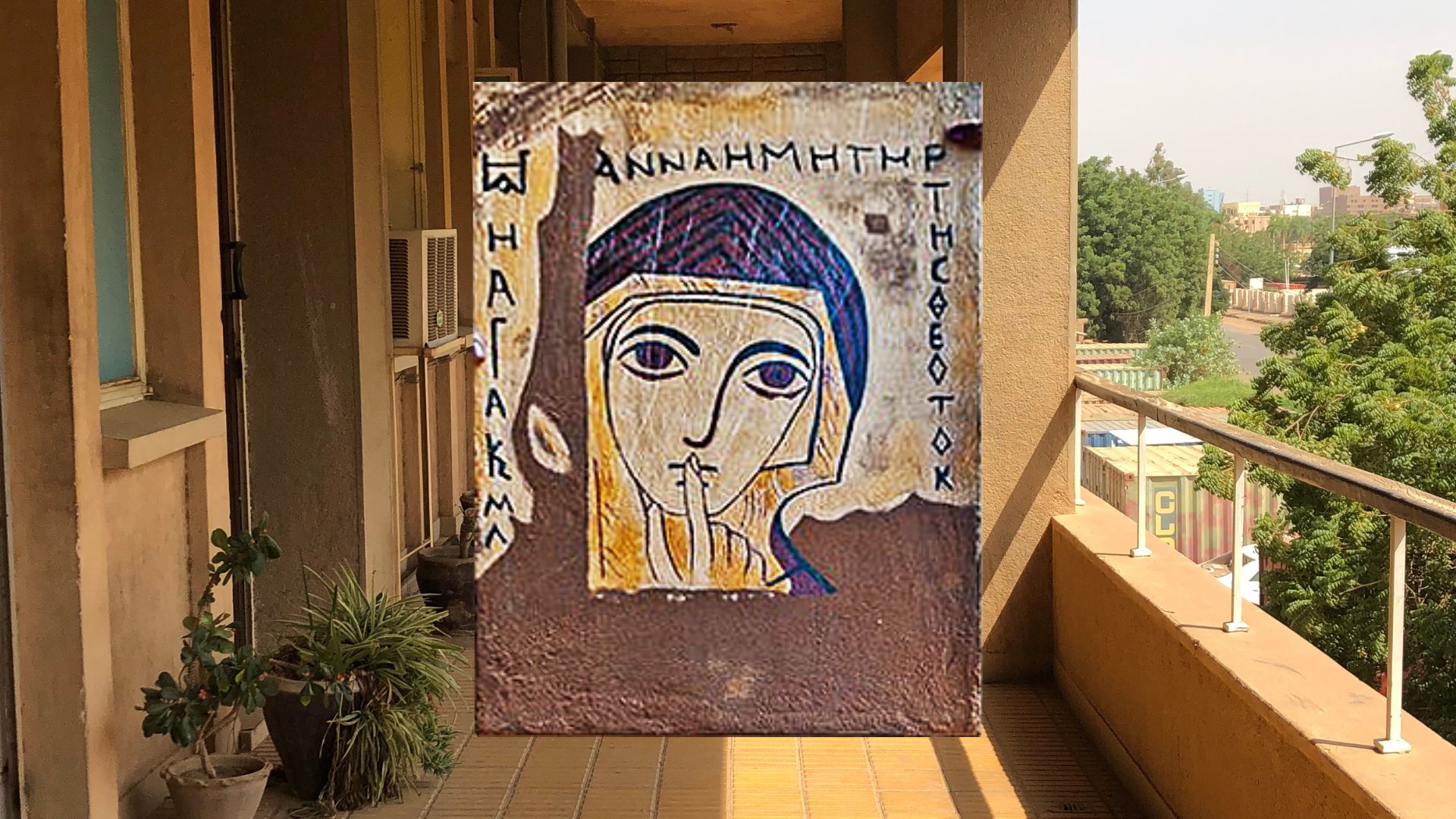

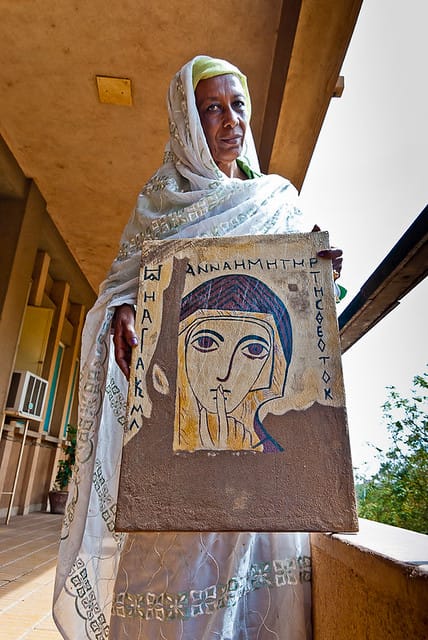

Samia Idris, the woman who documented history in silence

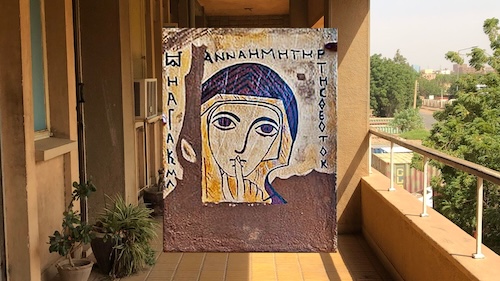

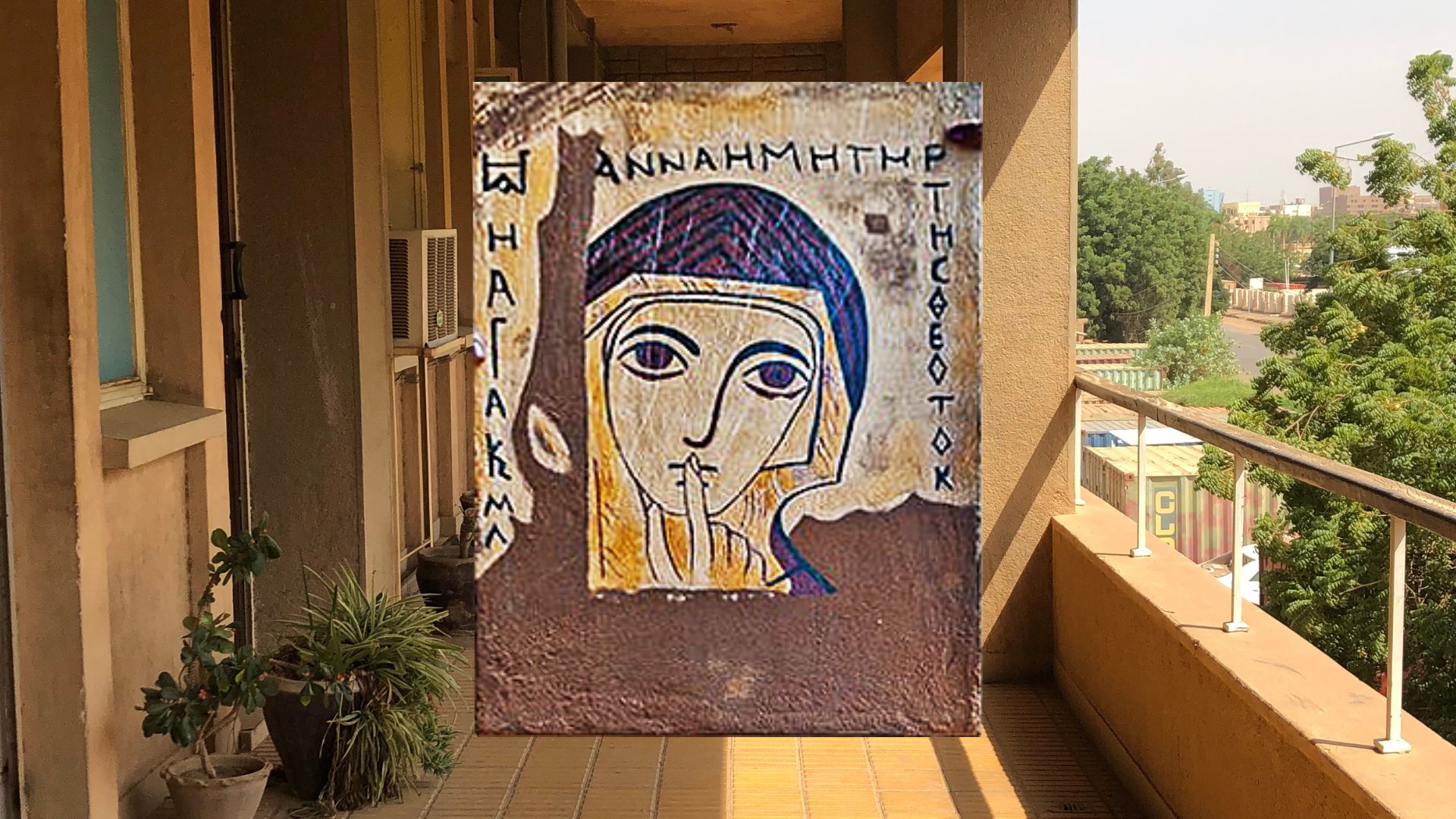

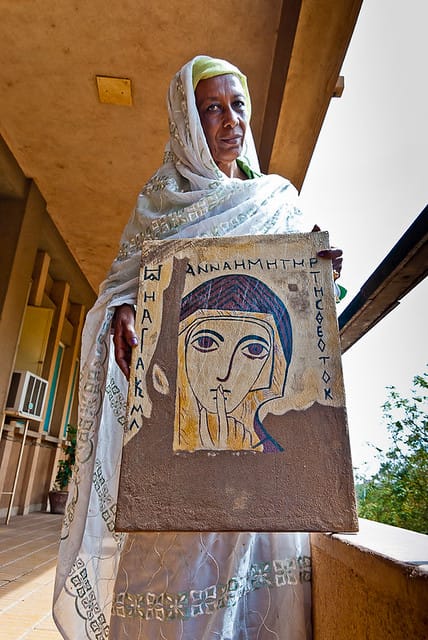

Samia Idris: the museum artist

Every morning the National Museum in Khartoum would open its doors, its corridors would be woken by the chatter of visitors, the steps of researchers and the hushed whisper of artefacts steeped in ancient history. In one of its less-visited corners, a woman would appear carrying a stack of papers and folders and a small bouquet of flowers. Silently, and with steady steps, she would head towards a clerk to hand him a flower, then she would give one to a cleaner and yet another to the guard at the museum entrance.

Her name was Samia Idris and she was head of the art department, but everyone knew her as the ‘flower lady’. Her words of greeting each morning were complemented by colour and fragrance. It was as if she was bringing life back into the museum before the day began.

Samia was a visual artist whose paintbrush and colours were tools for creating a space for artistic expression. Through a process of capturing and transforming, Samia documented artefacts where deeper meanings were revealed. She would study each artefact carefully and reinterpret it visually, making it visible in a way culture ought to be. In her quiet, professional manner, she documented the museum’s artefacts and rare collections to create a national archive that tells our story. Samia knew all of the museum’s galleries by heart and was able to remember the exact place of each piece of artwork and understood them as if they spoke to her in a common language. And when Samia sat at her desk and brought out her paint brush, she was able to restore the quality of the stones and give voice to the engravings.

What was most distinguished about her work was the quality of her paintings and how they recreated ancient works by adding missing details in order to produce meticulous replicas that were exhibited both at home and abroad in order to safeguard the originals from damage or loss. She would recreate missing details using colour and intuition and throughout her years of patient devotion, she never once signed any of her pieces but nevertheless, her presence was felt in everything.

In her painting 'Saint Anna,' she evoked motherhood, as portrayed in Sudanese Christian mythology, transforming the myth into a mother, and the mother into a story, to reconstruct a distant memory that was on the verge of being forgotten. In ‘Knight on Horseback’, she captured the nobility and heroism silently represented in ancient carvings showing how art can become an intimate disclosure. Her work was a bridge between preserving original artefacts and allowing people to see them afresh.

“Samia knew how to listen to stone, she did not see it as lifeless, but as a being that had lived and spoken, and so she became its translator,” recalls one of her old work colleagues. This is a fitting description of the woman who silently went about her work yet produced so much for others to enjoy. The first things her colleagues remember about Samia are her smile and flowers; “she would walk in every morning holding a flower as if she were spreading hope” says another colleague adding “she wasn’t just a colleague, she was a breath of fresh air.” Samia would stay long after hours, seated before an old painting, patiently tracing its weary details with her brush, and as night fell over Khartoum, she would continue to work to help document Sudan’s national memory.

Samia Idris: the poet

Samia was not only a talented artist, she was also a poet and a singer who saw the similarity between the two art forms in that they both served to restore, revive and enrich life. Through her words and in a firm but tender voice, Samia Idris advocated for peace. She did not care for politics. Instead, she addressed the human spirit, conscience and the memory of a scarred homeland. When she recited her verses which bore witness to wars but which gave hints of hope, her voice would rise up in a chant and then descend into soft reassurance. Her tone wavered between longing and protest, recounting wars not as abstract events, but as real sorrow etched onto the homeland. Samia spoke in a voice that resonated like the earth, sharing messages of peace in the belief that words could console and heal and that the simplest voice could soothe.

Peace

“We reached out our hands for peace,

And longed to embrace everyone.

We’ve had enough of digging trenches,

Enough of carrying guns.

We want peace,

So that we can take a step forward,

And be all right.”

In her composition ‘Peace,’ language and feeling intertwine as if she were singing to a Khartoum struggling for breath, or to a Nile wearied by spiritual drought. Her voice would rise to bear witness to the anguish of wars, then settle gently upon her listeners with words of hope and a call for reconciliation. Samia’s verses were well-known for their captivating simplicity.

City Streets

If you walk the city streets and see a woman gathering stones,

Know that she is a girl drowned by sorrow.

Time has bestowed upon her a necklace,

Its beads not of diamonds, but of rubies and dew drops,

Its thread spun from sinew and longing.

Here, Samia takes on the role of an embodied narrator—one who does not merely describe the city, but inhabits its sorrow, manifesting in the image of a simple woman gathering stones as if they were fragments of her own memory. Despite the simplicity of its language, the poem is laden with deep symbolism: the stones become a metaphor for sorrow, and the city a space of storytelling and survival against fracture.

This complex image of a woman crafting a necklace from sorrow, where dew drops and rubies become symbols, reflects what might be described as ‘affective feminine resistance’ where despite the pain, letting go is not an option. The poem carves out a tangible sorrow in tender language, turning cities, stones and suffering into feminine icons that each day walk, love and rise from their ruins. Using only a few meaningful words, she casts a gentle light on feminine pain, the kind that conceals itself behind the chores of everyday urban life. In the poem ‘City Streets,’ Samia transforms the act of gathering stones into a metaphor for inner turmoil, for sorrow dwelling in the body, and for the poisoned gifts that life may bestow upon women: a necklace of rubies and dew drops, strung with threads of sinew and longing. The short poem is subtle and is not lamenting in tone but gives the sorrowful woman who walks the streets a voice at once aching and graceful. In her fluid style, Samia shapes a poetic space rooted in the narrative of feminine pain without relinquishing the verse’s aesthetic beauty or sensual flow. In ‘City Streets,’ we do not merely see a girl gathering stones; we glimpse the memory of a homeland, a wounded femininity, and a silent resistance.

That was Samia; the flower lady, who came to the museum every morning with a bouquet of blooms in her arms and who left after dark after having done her work to safeguard a nation’s memory. Samia the artist, was the embodiment of every Sudanese woman: a mother, a widow, a teacher and an inspiration who raised her daughters and taught them that true glory can never be bought but is patiently woven out of the fine threads of endurance, labour, and honesty. Today, these daughters stand tall and are among the most accomplished women of their generation, each one carrying within her the spirit of a mother who never sought the spotlight nor longed for recognition. Samia Idris worked at the Sudan National Museum for many years, her presence there like that of a mother in the home, unseen yet ever-protective and even if she is hidden behind the machine of bureaucracy, her touch remains present in her canvases, words and memories.

In a moment of genuine emotion, I timidly composed the following in response Samia’s poem ‘City Streets.’

If you walk through the city streets and see a woman gathering stones,

Perhaps she is gathering a homeland—searching for its scattered edges,

For a museum that has lost its compass,

For colours no longer able to bear absence.

She paints not with words, but with the rare light she gathers.

The homeland is her mirror, and longing her truest lens.

This article has been a humble attempt to give back, not only to Samia, but to all those dedicated to the heritage sector who quietly document our history seeking no reward in return. For within every museum, there is a Samia… perhaps unseen, but always there.

Cover picture by Balsam Alqarih

Samia Idris, the woman who documented history in silence

Samia Idris: the museum artist

Every morning the National Museum in Khartoum would open its doors, its corridors would be woken by the chatter of visitors, the steps of researchers and the hushed whisper of artefacts steeped in ancient history. In one of its less-visited corners, a woman would appear carrying a stack of papers and folders and a small bouquet of flowers. Silently, and with steady steps, she would head towards a clerk to hand him a flower, then she would give one to a cleaner and yet another to the guard at the museum entrance.

Her name was Samia Idris and she was head of the art department, but everyone knew her as the ‘flower lady’. Her words of greeting each morning were complemented by colour and fragrance. It was as if she was bringing life back into the museum before the day began.

Samia was a visual artist whose paintbrush and colours were tools for creating a space for artistic expression. Through a process of capturing and transforming, Samia documented artefacts where deeper meanings were revealed. She would study each artefact carefully and reinterpret it visually, making it visible in a way culture ought to be. In her quiet, professional manner, she documented the museum’s artefacts and rare collections to create a national archive that tells our story. Samia knew all of the museum’s galleries by heart and was able to remember the exact place of each piece of artwork and understood them as if they spoke to her in a common language. And when Samia sat at her desk and brought out her paint brush, she was able to restore the quality of the stones and give voice to the engravings.

What was most distinguished about her work was the quality of her paintings and how they recreated ancient works by adding missing details in order to produce meticulous replicas that were exhibited both at home and abroad in order to safeguard the originals from damage or loss. She would recreate missing details using colour and intuition and throughout her years of patient devotion, she never once signed any of her pieces but nevertheless, her presence was felt in everything.

In her painting 'Saint Anna,' she evoked motherhood, as portrayed in Sudanese Christian mythology, transforming the myth into a mother, and the mother into a story, to reconstruct a distant memory that was on the verge of being forgotten. In ‘Knight on Horseback’, she captured the nobility and heroism silently represented in ancient carvings showing how art can become an intimate disclosure. Her work was a bridge between preserving original artefacts and allowing people to see them afresh.

“Samia knew how to listen to stone, she did not see it as lifeless, but as a being that had lived and spoken, and so she became its translator,” recalls one of her old work colleagues. This is a fitting description of the woman who silently went about her work yet produced so much for others to enjoy. The first things her colleagues remember about Samia are her smile and flowers; “she would walk in every morning holding a flower as if she were spreading hope” says another colleague adding “she wasn’t just a colleague, she was a breath of fresh air.” Samia would stay long after hours, seated before an old painting, patiently tracing its weary details with her brush, and as night fell over Khartoum, she would continue to work to help document Sudan’s national memory.

Samia Idris: the poet

Samia was not only a talented artist, she was also a poet and a singer who saw the similarity between the two art forms in that they both served to restore, revive and enrich life. Through her words and in a firm but tender voice, Samia Idris advocated for peace. She did not care for politics. Instead, she addressed the human spirit, conscience and the memory of a scarred homeland. When she recited her verses which bore witness to wars but which gave hints of hope, her voice would rise up in a chant and then descend into soft reassurance. Her tone wavered between longing and protest, recounting wars not as abstract events, but as real sorrow etched onto the homeland. Samia spoke in a voice that resonated like the earth, sharing messages of peace in the belief that words could console and heal and that the simplest voice could soothe.

Peace

“We reached out our hands for peace,

And longed to embrace everyone.

We’ve had enough of digging trenches,

Enough of carrying guns.

We want peace,

So that we can take a step forward,

And be all right.”

In her composition ‘Peace,’ language and feeling intertwine as if she were singing to a Khartoum struggling for breath, or to a Nile wearied by spiritual drought. Her voice would rise to bear witness to the anguish of wars, then settle gently upon her listeners with words of hope and a call for reconciliation. Samia’s verses were well-known for their captivating simplicity.

City Streets

If you walk the city streets and see a woman gathering stones,

Know that she is a girl drowned by sorrow.

Time has bestowed upon her a necklace,

Its beads not of diamonds, but of rubies and dew drops,

Its thread spun from sinew and longing.

Here, Samia takes on the role of an embodied narrator—one who does not merely describe the city, but inhabits its sorrow, manifesting in the image of a simple woman gathering stones as if they were fragments of her own memory. Despite the simplicity of its language, the poem is laden with deep symbolism: the stones become a metaphor for sorrow, and the city a space of storytelling and survival against fracture.

This complex image of a woman crafting a necklace from sorrow, where dew drops and rubies become symbols, reflects what might be described as ‘affective feminine resistance’ where despite the pain, letting go is not an option. The poem carves out a tangible sorrow in tender language, turning cities, stones and suffering into feminine icons that each day walk, love and rise from their ruins. Using only a few meaningful words, she casts a gentle light on feminine pain, the kind that conceals itself behind the chores of everyday urban life. In the poem ‘City Streets,’ Samia transforms the act of gathering stones into a metaphor for inner turmoil, for sorrow dwelling in the body, and for the poisoned gifts that life may bestow upon women: a necklace of rubies and dew drops, strung with threads of sinew and longing. The short poem is subtle and is not lamenting in tone but gives the sorrowful woman who walks the streets a voice at once aching and graceful. In her fluid style, Samia shapes a poetic space rooted in the narrative of feminine pain without relinquishing the verse’s aesthetic beauty or sensual flow. In ‘City Streets,’ we do not merely see a girl gathering stones; we glimpse the memory of a homeland, a wounded femininity, and a silent resistance.

That was Samia; the flower lady, who came to the museum every morning with a bouquet of blooms in her arms and who left after dark after having done her work to safeguard a nation’s memory. Samia the artist, was the embodiment of every Sudanese woman: a mother, a widow, a teacher and an inspiration who raised her daughters and taught them that true glory can never be bought but is patiently woven out of the fine threads of endurance, labour, and honesty. Today, these daughters stand tall and are among the most accomplished women of their generation, each one carrying within her the spirit of a mother who never sought the spotlight nor longed for recognition. Samia Idris worked at the Sudan National Museum for many years, her presence there like that of a mother in the home, unseen yet ever-protective and even if she is hidden behind the machine of bureaucracy, her touch remains present in her canvases, words and memories.

In a moment of genuine emotion, I timidly composed the following in response Samia’s poem ‘City Streets.’