The woman who documented history in silence

Her name was Samia Idris and she was head of the art department, but everyone knew her as the ‘flower lady’. Her words of greeting each morning were complemented by colour and fragrance. It was as if she was bringing life back into the museum before the day began.

/ answered

Samia Idris, the woman who documented history in silence

Samia Idris: the museum artist

Every morning the National Museum in Khartoum would open its doors, its corridors would be woken by the chatter of visitors, the steps of researchers and the hushed whisper of artefacts steeped in ancient history. In one of its less-visited corners, a woman would appear carrying a stack of papers and folders and a small bouquet of flowers. Silently, and with steady steps, she would head towards a clerk to hand him a flower, then she would give one to a cleaner and yet another to the guard at the museum entrance.

Her name was Samia Idris and she was head of the art department, but everyone knew her as the ‘flower lady’. Her words of greeting each morning were complemented by colour and fragrance. It was as if she was bringing life back into the museum before the day began.

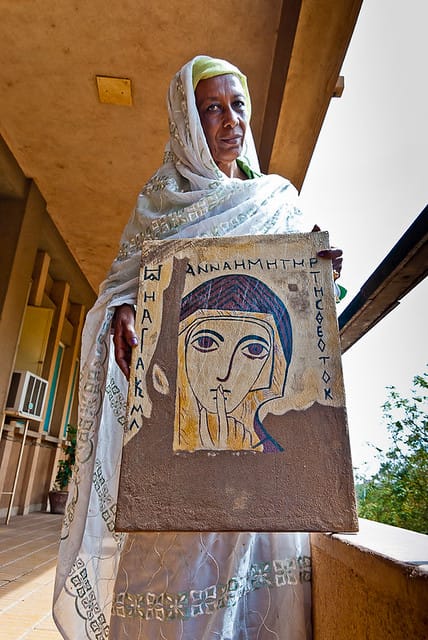

Samia was a visual artist whose paintbrush and colours were tools for creating a space for artistic expression. Through a process of capturing and transforming, Samia documented artefacts where deeper meanings were revealed. She would study each artefact carefully and reinterpret it visually, making it visible in a way culture ought to be. In her quiet, professional manner, she documented the museum’s artefacts and rare collections to create a national archive that tells our story. Samia knew all of the museum’s galleries by heart and was able to remember the exact place of each piece of artwork and understood them as if they spoke to her in a common language. And when Samia sat at her desk and brought out her paint brush, she was able to restore the quality of the stones and give voice to the engravings.

What was most distinguished about her work was the quality of her paintings and how they recreated ancient works by adding missing details in order to produce meticulous replicas that were exhibited both at home and abroad in order to safeguard the originals from damage or loss. She would recreate missing details using colour and intuition and throughout her years of patient devotion, she never once signed any of her pieces but nevertheless, her presence was felt in everything.

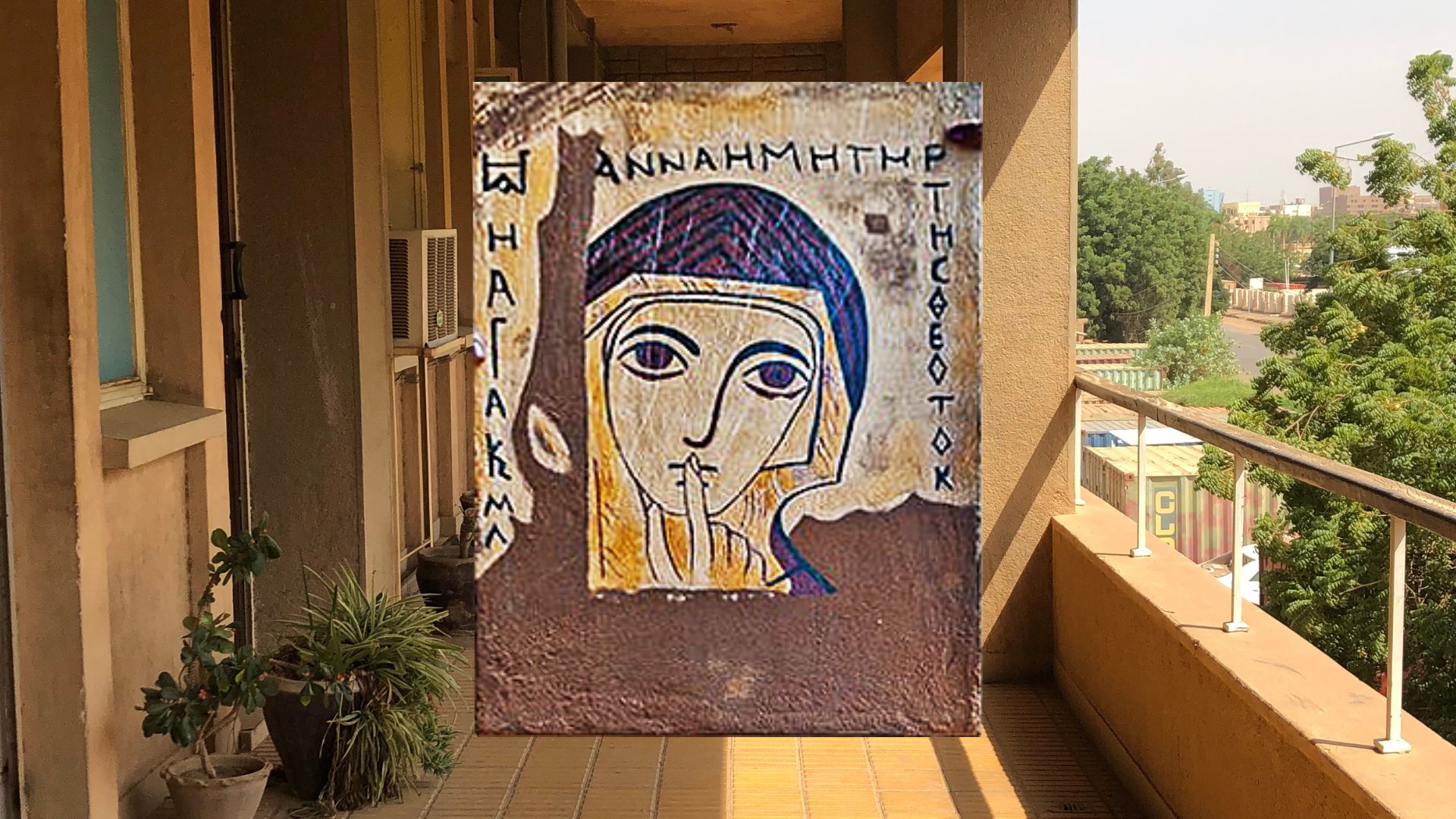

In her painting 'Saint Anna,' she evoked motherhood, as portrayed in Sudanese Christian mythology, transforming the myth into a mother, and the mother into a story, to reconstruct a distant memory that was on the verge of being forgotten. In ‘Knight on Horseback’, she captured the nobility and heroism silently represented in ancient carvings showing how art can become an intimate disclosure. Her work was a bridge between preserving original artefacts and allowing people to see them afresh.

“Samia knew how to listen to stone, she did not see it as lifeless, but as a being that had lived and spoken, and so she became its translator,” recalls one of her old work colleagues. This is a fitting description of the woman who silently went about her work yet produced so much for others to enjoy. The first things her colleagues remember about Samia are her smile and flowers; “she would walk in every morning holding a flower as if she were spreading hope” says another colleague adding “she wasn’t just a colleague, she was a breath of fresh air.” Samia would stay long after hours, seated before an old painting, patiently tracing its weary details with her brush, and as night fell over Khartoum, she would continue to work to help document Sudan’s national memory.

Samia Idris: the poet

Samia was not only a talented artist, she was also a poet and a singer who saw the similarity between the two art forms in that they both served to restore, revive and enrich life. Through her words and in a firm but tender voice, Samia Idris advocated for peace. She did not care for politics. Instead, she addressed the human spirit, conscience and the memory of a scarred homeland. When she recited her verses which bore witness to wars but which gave hints of hope, her voice would rise up in a chant and then descend into soft reassurance. Her tone wavered between longing and protest, recounting wars not as abstract events, but as real sorrow etched onto the homeland. Samia spoke in a voice that resonated like the earth, sharing messages of peace in the belief that words could console and heal and that the simplest voice could soothe.

Peace

“We reached out our hands for peace,

And longed to embrace everyone.

We’ve had enough of digging trenches,

Enough of carrying guns.

We want peace,

So that we can take a step forward,

And be all right.”

In her composition ‘Peace,’ language and feeling intertwine as if she were singing to a Khartoum struggling for breath, or to a Nile wearied by spiritual drought. Her voice would rise to bear witness to the anguish of wars, then settle gently upon her listeners with words of hope and a call for reconciliation. Samia’s verses were well-known for their captivating simplicity.

City Streets

If you walk the city streets and see a woman gathering stones,

Know that she is a girl drowned by sorrow.

Time has bestowed upon her a necklace,

Its beads not of diamonds, but of rubies and dew drops,

Its thread spun from sinew and longing.

Here, Samia takes on the role of an embodied narrator—one who does not merely describe the city, but inhabits its sorrow, manifesting in the image of a simple woman gathering stones as if they were fragments of her own memory. Despite the simplicity of its language, the poem is laden with deep symbolism: the stones become a metaphor for sorrow, and the city a space of storytelling and survival against fracture.

This complex image of a woman crafting a necklace from sorrow, where dew drops and rubies become symbols, reflects what might be described as ‘affective feminine resistance’ where despite the pain, letting go is not an option. The poem carves out a tangible sorrow in tender language, turning cities, stones and suffering into feminine icons that each day walk, love and rise from their ruins. Using only a few meaningful words, she casts a gentle light on feminine pain, the kind that conceals itself behind the chores of everyday urban life. In the poem ‘City Streets,’ Samia transforms the act of gathering stones into a metaphor for inner turmoil, for sorrow dwelling in the body, and for the poisoned gifts that life may bestow upon women: a necklace of rubies and dew drops, strung with threads of sinew and longing. The short poem is subtle and is not lamenting in tone but gives the sorrowful woman who walks the streets a voice at once aching and graceful. In her fluid style, Samia shapes a poetic space rooted in the narrative of feminine pain without relinquishing the verse’s aesthetic beauty or sensual flow. In ‘City Streets,’ we do not merely see a girl gathering stones; we glimpse the memory of a homeland, a wounded femininity, and a silent resistance.

That was Samia; the flower lady, who came to the museum every morning with a bouquet of blooms in her arms and who left after dark after having done her work to safeguard a nation’s memory. Samia the artist, was the embodiment of every Sudanese woman: a mother, a widow, a teacher and an inspiration who raised her daughters and taught them that true glory can never be bought but is patiently woven out of the fine threads of endurance, labour, and honesty. Today, these daughters stand tall and are among the most accomplished women of their generation, each one carrying within her the spirit of a mother who never sought the spotlight nor longed for recognition. Samia Idris worked at the Sudan National Museum for many years, her presence there like that of a mother in the home, unseen yet ever-protective and even if she is hidden behind the machine of bureaucracy, her touch remains present in her canvases, words and memories.

In a moment of genuine emotion, I timidly composed the following in response Samia’s poem ‘City Streets.’

If you walk through the city streets and see a woman gathering stones,

Perhaps she is gathering a homeland—searching for its scattered edges,

For a museum that has lost its compass,

For colours no longer able to bear absence.

She paints not with words, but with the rare light she gathers.

The homeland is her mirror, and longing her truest lens.

This article has been a humble attempt to give back, not only to Samia, but to all those dedicated to the heritage sector who quietly document our history seeking no reward in return. For within every museum, there is a Samia… perhaps unseen, but always there.

Cover picture by Balsam Alqarih

Samia Idris, the woman who documented history in silence

Samia Idris: the museum artist

Every morning the National Museum in Khartoum would open its doors, its corridors would be woken by the chatter of visitors, the steps of researchers and the hushed whisper of artefacts steeped in ancient history. In one of its less-visited corners, a woman would appear carrying a stack of papers and folders and a small bouquet of flowers. Silently, and with steady steps, she would head towards a clerk to hand him a flower, then she would give one to a cleaner and yet another to the guard at the museum entrance.

Her name was Samia Idris and she was head of the art department, but everyone knew her as the ‘flower lady’. Her words of greeting each morning were complemented by colour and fragrance. It was as if she was bringing life back into the museum before the day began.

Samia was a visual artist whose paintbrush and colours were tools for creating a space for artistic expression. Through a process of capturing and transforming, Samia documented artefacts where deeper meanings were revealed. She would study each artefact carefully and reinterpret it visually, making it visible in a way culture ought to be. In her quiet, professional manner, she documented the museum’s artefacts and rare collections to create a national archive that tells our story. Samia knew all of the museum’s galleries by heart and was able to remember the exact place of each piece of artwork and understood them as if they spoke to her in a common language. And when Samia sat at her desk and brought out her paint brush, she was able to restore the quality of the stones and give voice to the engravings.

What was most distinguished about her work was the quality of her paintings and how they recreated ancient works by adding missing details in order to produce meticulous replicas that were exhibited both at home and abroad in order to safeguard the originals from damage or loss. She would recreate missing details using colour and intuition and throughout her years of patient devotion, she never once signed any of her pieces but nevertheless, her presence was felt in everything.

In her painting 'Saint Anna,' she evoked motherhood, as portrayed in Sudanese Christian mythology, transforming the myth into a mother, and the mother into a story, to reconstruct a distant memory that was on the verge of being forgotten. In ‘Knight on Horseback’, she captured the nobility and heroism silently represented in ancient carvings showing how art can become an intimate disclosure. Her work was a bridge between preserving original artefacts and allowing people to see them afresh.

“Samia knew how to listen to stone, she did not see it as lifeless, but as a being that had lived and spoken, and so she became its translator,” recalls one of her old work colleagues. This is a fitting description of the woman who silently went about her work yet produced so much for others to enjoy. The first things her colleagues remember about Samia are her smile and flowers; “she would walk in every morning holding a flower as if she were spreading hope” says another colleague adding “she wasn’t just a colleague, she was a breath of fresh air.” Samia would stay long after hours, seated before an old painting, patiently tracing its weary details with her brush, and as night fell over Khartoum, she would continue to work to help document Sudan’s national memory.

Samia Idris: the poet

Samia was not only a talented artist, she was also a poet and a singer who saw the similarity between the two art forms in that they both served to restore, revive and enrich life. Through her words and in a firm but tender voice, Samia Idris advocated for peace. She did not care for politics. Instead, she addressed the human spirit, conscience and the memory of a scarred homeland. When she recited her verses which bore witness to wars but which gave hints of hope, her voice would rise up in a chant and then descend into soft reassurance. Her tone wavered between longing and protest, recounting wars not as abstract events, but as real sorrow etched onto the homeland. Samia spoke in a voice that resonated like the earth, sharing messages of peace in the belief that words could console and heal and that the simplest voice could soothe.

Peace

“We reached out our hands for peace,

And longed to embrace everyone.

We’ve had enough of digging trenches,

Enough of carrying guns.

We want peace,

So that we can take a step forward,

And be all right.”

In her composition ‘Peace,’ language and feeling intertwine as if she were singing to a Khartoum struggling for breath, or to a Nile wearied by spiritual drought. Her voice would rise to bear witness to the anguish of wars, then settle gently upon her listeners with words of hope and a call for reconciliation. Samia’s verses were well-known for their captivating simplicity.

City Streets

If you walk the city streets and see a woman gathering stones,

Know that she is a girl drowned by sorrow.

Time has bestowed upon her a necklace,

Its beads not of diamonds, but of rubies and dew drops,

Its thread spun from sinew and longing.

Here, Samia takes on the role of an embodied narrator—one who does not merely describe the city, but inhabits its sorrow, manifesting in the image of a simple woman gathering stones as if they were fragments of her own memory. Despite the simplicity of its language, the poem is laden with deep symbolism: the stones become a metaphor for sorrow, and the city a space of storytelling and survival against fracture.

This complex image of a woman crafting a necklace from sorrow, where dew drops and rubies become symbols, reflects what might be described as ‘affective feminine resistance’ where despite the pain, letting go is not an option. The poem carves out a tangible sorrow in tender language, turning cities, stones and suffering into feminine icons that each day walk, love and rise from their ruins. Using only a few meaningful words, she casts a gentle light on feminine pain, the kind that conceals itself behind the chores of everyday urban life. In the poem ‘City Streets,’ Samia transforms the act of gathering stones into a metaphor for inner turmoil, for sorrow dwelling in the body, and for the poisoned gifts that life may bestow upon women: a necklace of rubies and dew drops, strung with threads of sinew and longing. The short poem is subtle and is not lamenting in tone but gives the sorrowful woman who walks the streets a voice at once aching and graceful. In her fluid style, Samia shapes a poetic space rooted in the narrative of feminine pain without relinquishing the verse’s aesthetic beauty or sensual flow. In ‘City Streets,’ we do not merely see a girl gathering stones; we glimpse the memory of a homeland, a wounded femininity, and a silent resistance.

That was Samia; the flower lady, who came to the museum every morning with a bouquet of blooms in her arms and who left after dark after having done her work to safeguard a nation’s memory. Samia the artist, was the embodiment of every Sudanese woman: a mother, a widow, a teacher and an inspiration who raised her daughters and taught them that true glory can never be bought but is patiently woven out of the fine threads of endurance, labour, and honesty. Today, these daughters stand tall and are among the most accomplished women of their generation, each one carrying within her the spirit of a mother who never sought the spotlight nor longed for recognition. Samia Idris worked at the Sudan National Museum for many years, her presence there like that of a mother in the home, unseen yet ever-protective and even if she is hidden behind the machine of bureaucracy, her touch remains present in her canvases, words and memories.

In a moment of genuine emotion, I timidly composed the following in response Samia’s poem ‘City Streets.’

If you walk through the city streets and see a woman gathering stones,

Perhaps she is gathering a homeland—searching for its scattered edges,

For a museum that has lost its compass,

For colours no longer able to bear absence.

She paints not with words, but with the rare light she gathers.

The homeland is her mirror, and longing her truest lens.

This article has been a humble attempt to give back, not only to Samia, but to all those dedicated to the heritage sector who quietly document our history seeking no reward in return. For within every museum, there is a Samia… perhaps unseen, but always there.

Cover picture by Balsam Alqarih

.svg)